A spinal cord injury occurs with a sudden, traumatic blow to the spine that fractures or dislocates vertebrae. The leading reason for spinal injury includes vehicular accidents, falls, acts of violence and sporting injuries. The degree of injury would determine the neurological deficit the patient is getting ready to face.

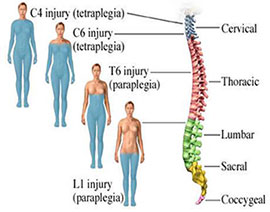

Most common location of the injury

The most common vertebrae involved in Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) are the 5th, 6th and 7th cervical, the 12th thoracic, and the 1st lumbar.

Classification

Spinal Cord Injury can be separated into two categories:

- Primary injury is caused by direct trauma and may result in permanent usually.

- Secondary injury is cause by tear injury, in which the nerve fibers begin to swell and disintegrate. (Sherwood, et al. 2007)

Types of Injury

- Complete injury – there’s no function below the extent of the injury; no sensation and no voluntary movement. Either side of the body are equally affected.

- Incomplete injury – there’s some functioning below the first level of the injury. An individual with an incomplete injury is also able to move one limb over another, is also able to feel parts of the body that can’t be moved, or may have more acting on one side of the body than the opposite.

Prevalence according to the National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center (2020)

Current estimates are 250,000 – 368,000 individuals living with Spinal Cord Injury or Spinal Dysfunction.

- 78% male, 22% female

- Highest occurs between ages 16-30

- The average age at injury is 29

Risk factors

Motor vehicle crashes account for 48% of reported cases of SCI, with falls (23%), violence primarily from gunshot wounds (14%), recreational sporting activities (9%) and other events accounting for the remaining injuries.

Causes

- Hard impacts and collisions in sports

- Automobile accidents

- Falls

- Hitting the head when diving

- Injuries from violent acts, such as gunshot wounds

- Certain types of cancer

- Arthritis

- Specific types of infections

- Some medical conditions, such as spina bifida and polio

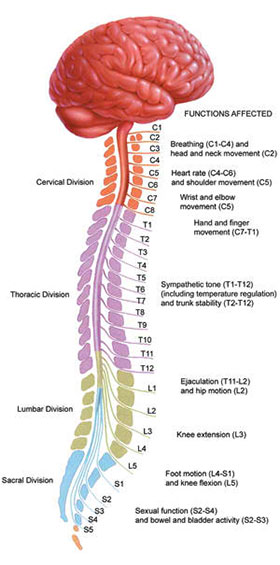

Signs and symptoms

Long-term – People who have spinal cord injuries may have some or all of the following symptoms throughout their life:

- loss of movement of certain parts of the body

- loss of feeling or change in feeling

- loss of bowel or bladder control

- pain, which can range from mild to severe

- muscle spasms

- abnormal reflexes

- loss of sexual function

- infertility

- trouble walking or maintaining balance

- difficulty breathing or coughing

Emergency signs and symptoms

- Fading in and out of consciousness

- Extreme back pain and pressure in neck or back

- Weakness/paralysis

- Numbness

- Loss of bladder and bowel control

- Difficulty with balance and walking

- Impaired breathing

- An oddly positioned twisted neck or body

Complications

- Loss of bladder control, bowel control, or both – Patients with spinal cord injury cannot feel the urge to go so they may need to learn how to empty their bladder or they may need to use devices to help them such as the use of a foley catheter or diaper.

- Loss of muscle tone – Muscles shrink and becomes weak when they are not in use. Patient is encouraged to attend physical rehabilitation to prevent the progress of muscle atrophy.

- Muscle spasms – Sometimes, uncontrolled muscle movements and spasticity happen when muscles contract in patients with SCI.

- Nerve pain – Long-term nerve pain may occur in parts of the body that still have feeling or little sensation.

- Skin sores and injuries – Patient may not feel any sores, cuts, or burns as they happen due to the lack of tactile sensation. Frequent assessment of the patient is needed to prevent this.

- Lung problems – Some spinal cord injuries can cause partial or full paralysis if the lungs. This affects that patient’s ability to breathe and cough. This puts them in higher risk of getting pneumonia.

- Stroke and cardiac arrest – There is a risk of the blood pressure suddenly going dangerously high which may lead to seizures, heart attack, and stroke.

- Infertility – Women may have a difficulty in getting pregnant and sometimes prevent ejaculation in males.

- Deep Vein Thromobosis – Usually occurs in patients that are immobile. This is a clot formation that is trapped usually in the legs that prevent patent blood flow to the lower extremities.

- Autonomic Dysreflexia is caused exaggerated autonomic responses to stimuli. Clinical manifestations to watch out for are severe pounding headache with paroxysmal hypertension, profuse diaphoresis, nausea, nasal congestion and bradycardia. The sudden increase in blood pressure may rupture one or more cerebral blood vessels or lead to increased ICP.

Management for Autonomic Dyreflexia

- Place immediately in sitting position

- Urinary catheter is immediately used in emptying the bladder

- Rectum should be examined for fecal mass

- Any other triggering stimulus should be removed

- A ganglionic blocking agent is prescribed and administered slowly by the IV route

4 Spinal Cord Injury Nursing Care Plan based on NANDA

1

| Nursing Intervention | Rationale |

| Independent:

Note client’s level of injury when assessing respiratory function. Note presence or absence of spontaneous effort and quality of respiration. (e.g. labored, using accessory muscles)

|

Injuries at C5 can result in variable loss of respiratory function, depending on the phrenic nerve involvement and diaphragmatic function but generally cause decreased vital capacity and inspiratory effort. |

| Auscultate breath sounds. Note areas of absent or decreased breath sounds or development of adventitious sounds.

|

Hypoventilation is common and leads to accumulation of secretions, atelectasis and pneumonia. |

| Maintain client airway: keep head in neutral position, elevate head of bed slightly if tolerated, and use airway adjunct as indicated.

|

Clients with high cervical injury and impaired cough reflex needs assistance in preventing aspiration/maintaining patent airway. |

| Assist client in taking control of respirations as indicated. Instruct and encourage deep breathing focusing attention on steps of breathing. | Breathing may no longer be a totally involuntary activity but require conscious effort, depending on level of injury/involvement of respiratory muscles. |

| Maintain a calm attitude, assisting client to “take control” by using slower/deeper respirations. | Assist client to dela with the physiologic effects of hypoxia which may be manifested as anxiety and fear. |

| Assist with coughing as indicated for level of injury; e.g have client take deep breath for 2 sec. before coughing, or inhale deeply then cough at the end of a slow exhalation. Alternatively assist by placing hands below diaphragm and pushing upward as client exhales. | ) Adds volume to cough and facilitates expectoration of secretions or help move them high enough to be suctioned out. |

| Reposition/turn periodically. Avoid/limit prone position when indicated. | Enhances ventilation of all lung segments, mobilizes secretions, reducing risk of infection. Note: prone position significantly decreases vital capacity, and increase risk of resp. compromise failure. |

| Encourage patient to fluids (at least 2000ml/day). | Aids liquefying secretions, promoting mobilization and expectoration. |

| Assist with use of respiratory adjuncts: incentive spirometer | Preventing retained secretions is essential to maximize gas diffusion. |

| Collaborative:

Administer oxygen by appropriate method. (Nasal cannula) |

Method determine by level of injury, degree of respiratory insufficiency. |

| Check serial ABGs. | Document status of ventilation and oxygenation, identifies respiratory problems. |

2

| Nursing Intervention | Rationale |

| Independent:

Continually assess motor function by requesting client to perform certain actions (e.g, shrug shoulders, spread fingers, release/squeeze examiner’s hands) |

Evaluates status of individual situation (motor-sensory impairment may be mixed and or not clear) for a specific level of injury, affecting type and choice of interventions. |

| Perform/assist with full ROM exercises on all extremities and joints, using slow smooth movements. Hyperextend hips periodically. | Enhances circulation, restores/maintains muscle tone and joint mobility and prevents disuse contractures and muscle atrophy. |

| Position arms at 90 degree at regular intervals. | Prevents frozen shoulder contractures. |

| Maintain ankles at 90 degree with footboard. Place trochanter rolls along thighs when in bed. | Prevents foot drop and external rotation of hips. |

| Assess skin daily. Observe for pressure areas and provide meticulous skin care. | Altered circulation, loss of sensation, and paralysis potentiate pressure sore formation. |

| Assess for redness, swelling/muscle tension of calf tissues. Record calf and thigh measurements as indicated. | In a high percentage of clients with cervical cord injury, thrombi develop because of altered peripheral circulation, immobilization, and flaccid paralysis. Greatest during 2 weeks but persist throughout life span. |

| Investigate sudden onset of dyspnea, cyanosis, and other signs of resp. distress. | Development of pulmonary emboli may be silent because pain is altered and DVT is not easily recognized. |

| Collaborative:

Administer medication as indicated Baclofen (Lioresal) 10 mg/tab TID as ordered by the physician. |

May be useful for reducing pain associated with spasticity. Note: Baclofen may be delivered via implanted intrathecal pump on a long term basis as appropriate. |

3

| Nursing Intervention | Rationale |

| Assessment Identify/monitor precipitating risk factors; e.g, bladder/bowel distention or manipulation; bladder spams, stones, infection; skin/tissue pressure areas, prolonged sitting position, temperature extremes/drafts. | Visceral distention is the most common cause of autonomic dysreflexia which is considered an emergency. Treatment of acute episode must be carried out immediately (removing stimulus, treating unresolved symptoms), the interventions must be geared toward prevention. |

| Observe for signs/symptoms of syndrome: e.g changes in VS, paroxysmal hypertension, tachycardia/bradycardia; autonomic responses: sweating, flushing above level of lesion; pallor below injury, chills, goose flesh, piloerection, nasal stuffiness, severe pounding headache, especially in occiput and frontal regions. Note associated symptoms: chest pains, blurred vision, nausea, metallic taste, Horner’s syndrome (contraction of pupil, partial stasis of eyelid, enophthalmos (recession of eyeball into the orbit), and sometimes loss of sweating over one side of the face). | Early detection and immediate intervention is essential to prevent serious consequences/complications. Note: Average systolic BP in tetraplegic client after spinal shock has resolved is 120; therefore readings of 140+ are considered high. |

| Independent Monitor BP frequently (every 3-5) during acute autonomic dysreflexia and take action to eliminate stimulus. Continue to monitor BP at intervals after symptoms subside. | Aggressive therapy/removal of stimulus may drop BP rapidly resulting in a hypotensive crisis, especially in those clients who routinely have low BP. In addition autonomic dysreflexia may recur, particularly if stimulus is not eliminated. |

| Correct/eliminate causative stimulus as able; e.g., bladder, bowel, skin pressure (including loosening tight leg bands/clothing, removing abdominal binder/elastic stockings; temperature extremes. | Removing noxious stimulus usually terminated episode and may prevent more serious autonomic dysreflexia. |

| Inform client/SO of warning signals and how to avoid onset of symptoms; e.g goose flesh, sweating, piloerection may indicate full bowel; sunburn may precipitate episode. | This lifelong problem can largely controlled by avoiding pressure from over distention of visceral organs or pressure on the skin. |

4

| Nursing Intervention | Rationale |

| Independent:

Inspect all skin areas, noting capillary blanching/refill, redness, and swelling. Pay particular attention to back of head and folds where skin continuously touches. |

Skin is especially prone to breakdown because of changes in peripheral circulation, inability to sense pressure, immobility, altered temperature regulation. |

| Elevate lower extremities periodically, if tolerated.

|

Enhances venous return. Reduces edema formation. |

| Massage and lubricate skin with bland lotion/oil. Protect pressure points by use of heel/elbow pads, lamb’s wool, foam padding, egg-crate mattress. | Enhances circulation and protects skin surfaces, reducing risk of ulceration. Tetraplegic and paraplegic patients require lifelong protection from decubitus formation, which can cause extensive tissue necrosis and sepsis |

| Reposition frequently, whether in bed or in sitting position. Place in prone position periodically. | Improves skin circulation and reduces pressure time on bony prominences. |

| Wash and dry skin, especially in high moisture areas such as perineum. | Clean, dry skin is less prone to excoriation/ breakdown. |

| Keep bedclothes dry and free of wrinkles, crumbs. | Reduces/ prevents skin irritation |

| Provide kinetic therapy or alternating-pressure mattress as indicated. | Improves systemic and peripheral circulation and decreases pressure on skin, reducing risk of breakdown. |

| Collaborative:

Avoid/limit injection of medication below the level of injury. |

Reduced circulation and sensation increase risk of delayed absorption, local reaction, and tissue necrosis. |

| Encourage continuation of regular exercise program. | Stimulates circulation, enhancing cellular nutrition/ oxygenation to improve tissue health. |

Some patients may recover, some may retrieve few motor functions and some stays paralyze. It is a challenging and lifelong complication that needs to be addressed by the patient’s caregiver. An inter-disciplinary team must be coordinated to facilitate face and adequate recovery.

Reference

- Doenges, M. E., Moorhouse, M. F., & Murr, A. C. (2006). Nurse’s pocket guide: Diagnoses, prioritized interventions, and rationales. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

- Hinkle, J. L. (2014). Brunner & Suddarth’s textbook of medical-surgical nursing (Edition 13.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Spinal Cord Injury Facts and Figures at a Glance. (2020). Retrieved May 3, 2020, from https://www.nscisc.uab.edu/Public/Facts and Figures 2020.pdf

This page was last edited on 29 May 2020

![[Stroke] Cerebrovascular Accident Nursing Care Plan cerebrovascular accident nursing care plan](https://rnspeak.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/CVA-nursing-care-plan-238x178.jpg)